The Truth About Virtual Fencing: Unreliable GPS, Emotional Fallout, and Why It Fails Dogs

Introduction

Virtual fencing is often marketed as a high-tech, humane way to contain animals, offering flexibility without the need for physical barriers. However, research highlights serious flaws in accuracy, reliability, and its impact on animal welfare—especially for dogs.

Three major concerns emerge from recent studies:

📍 GPS Inaccuracy – Positioning errors cause virtual fences to fail at enforcing reliable boundaries.

📍 Unpredictable Corrections – Dogs may receive electric shocks even when inside their designated safe zone.

📍 Emotional & Behavioral Damage – The unpredictability of corrections destroys a dog’s sense of felt safety and trust in their guardian.

Let’s break down what the science says about why virtual fencing is neither safe nor effective for dogs.

🐾🐾🐾

Study 1: How Inaccurate is GPS?

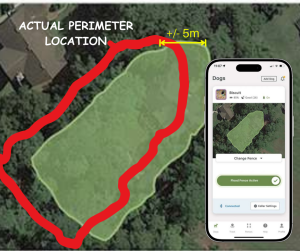

A study by Muminov et al. (2019) examined GPS errors in virtual fencing smart collars, revealing alarming inaccuracies:

- GPS errors ranged from 10 to 190 meters (33 to 623 feet).

- Weather, satellite positioning, and obstacles worsened accuracy.

- Unreliable positioning led to animals being incorrectly shocked.

What This Means for Dogs:

📍 A dog could be inside the virtual fence but still receive a shock due to GPS drift.

📍 Since satellite signals shift throughout the day, the dog’s perceived location changes unpredictably.

📍 This creates anxiety and damages trust—dogs never know when the next correction is coming.

Study 2: What Happens When Virtual Fencing Fails?

A 2016 study by Thin et al. examined failure rates of GPS tracking systems, finding:

- Ionospheric interference caused errors up to ±5 meters (16 feet).

- Multipath signal reflection (e.g., bouncing off buildings or trees) added another 1-3 meters (3-10 feet) of error.

- Urban and suburban environments had significantly worse accuracy.

🔴 The biggest problem? Virtual fences “move” throughout the day, creating an invisible, shifting boundary that dogs can’t predict or trust.

What This Means for Dogs:

🐕 Felt Safety is Destroyed: If a dog can’t predict where their safe space is, they may become anxious or hesitant to move.

🚫 Boundary Training Fails: Unlike real fences, which provide clear, consistent boundaries, virtual fences just punish mistakes.

💔 Separation Anxiety Risk: Repeated shocks when trying to approach home damage a dog’s sense of security with their guardian.

🐾🐾🐾

Study 3: Can Virtual Fencing Be “Fixed” with Better GPS?

A study by Verdon et al. (2021) attempted to improve virtual fencing for dairy heifers by pre-exposing them to electric fences. Their results?

- Shocks decreased over time, but learning was inconsistent—some animals continued getting shocked unnecessarily.

- Animals previously exposed to shock-based training learned faster—suggesting they had already developed a stress response.

- The study failed to measure emotional impact, ignoring the psychological cost of repeated exposure to shocks.

🚨 Key ethical issue: Less punishment over time doesn’t make a system humane—the initial punishment itself is unnecessary and harmful.

What This Means for Dogs:

What This Means for Dogs:

🐕 Unlike livestock, dogs form deep emotional bonds with humans—shocking them damages trust and emotional security.

🚫 Dogs do not learn well through avoidance-based methods—fear-based training leads to anxiety, aggression, or learned helplessness.

💔 Felt safety is critical for a well-adjusted dog—shocking them into compliance only creates trauma.

🐾🐾🐾

Helplessness

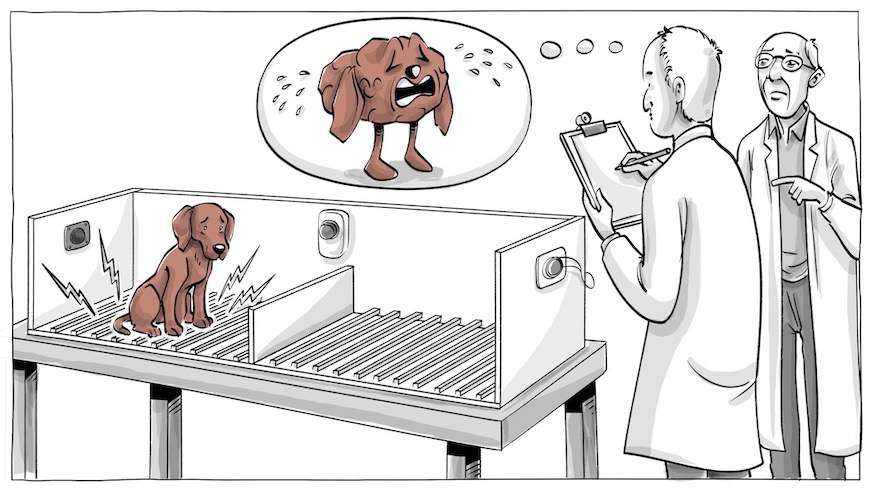

The concept of learned helplessness was first described by Seligman & Maier (1967) in experiments where dogs exposed to inescapable shocks stopped trying to escape—even when escape became possible.

- Lindsay (2000) explained how non-contingent aversive stimulation (such as shock collars) leads to learned helplessness, where dogs shut down emotionally due to unpredictable pain.

- Dogs in these studies developed motivational and behavioral deficits, which parallels the impact of virtual fencing.

🔴 Key Takeaway: If a dog cannot predict or control when a shock happens, they may stop exploring, engaging, or even responding to their guardian.

🐾🐾🐾

The Do No Harm Perspective: Why Shock-Free Training is Essential

“The use of equipment causing stress or pain, such as choke, prong, or electronic shock collars is antithetical to Do No Harm training and is harmful to dogs.”

— Michaels, 2022, p. 116

🚫 GPS fences create fear, not understanding. Choose humane, trust-based training instead!

📖 Learn more from Linda Michaels’ book:

The Do No Harm Dog Training and Behavior Handbook: Featuring the Hierarchy of Dog Needs®

📚 Available on Amazon: https://amzn.to/3Z6XhcZ

🐾🐾🐾

Final Thoughts

Virtual fencing isn’t just inaccurate—it actively harms a dog’s mental and emotional well-being. GPS errors make boundaries unpredictable, and shocking a dog when they don’t understand why destroys their trust, confidence, and security.

If you’re looking for a humane way to teach your dog boundaries, I can help. My approach is based on trust, relationship-building, and non-aversive techniques that empower your dog instead of punishing them.

📅 Book a consultation: https://holisticdogtraining.as.me/Short-Web

🐾🐾🐾

References

📌 Michaels, L. (2022). The Do No Harm Dog Training and Behavior Handbook: Featuring the Hierarchy of Dog Needs®. Do No Harm Dog Training.

📌 China, L., Mills, D. S., & Cooper, J. J. (2020). Efficacy of dog training with and without remote electronic collars vs. a focus on positive reinforcement. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00508

📌 Lindsay, S. R. (2000). Handbook of applied dog behavior and training. Iowa State University Press.

📌 Seligman, M. E. P., & Maier, S. F. (1967). Failure to escape traumatic shock. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 74(1), 1-9.

📌 Muminov, A., et al. (2019). Reducing GPS error for smart collars based on animal behavior. Applied Sciences, 9(16), 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9163408